Corner Shop

Babita Sharma

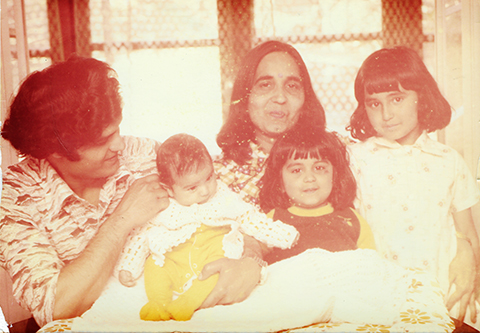

I am a corner-shop kid. We – a family of five – ate, slept, lived and worked in the shop. We served you and you gave us business, but there was a world beyond the counter that you never knew.

Perhaps your local shopkeeper resembles my mum and dad: born in India, they were shopkeepers for more than 20 years. Whoever it is, they have taken on a role that remains firmly entrenched in British life.

The shop on the corner evolved as a way to service communities in post-war Britain and became something much more significant: any family taking on the corner shop was instantly propelled into the frontline of community life.

My parents’ foray into this world was more about opportunity than about some inherent link between Asians and local shops. They wanted to work for themselves and the corner shop provided a solution.

But running a shop is a gruelling regime – and a corner shop takes more than one family to run it. It requires community support, regular customers and friendly neighbours to ease the burden of the seven days a week, open all hours culture.

Our yearning for reliable, easy-access shopping is bringing us back to the door of the trusted corner shop. During the pandemic, we headed to the local as if we had been regular customers for years, grabbing essential supplies of toilet rolls, flour and anti-bac gel. Corner shops, once again, were there to serve us unconditionally at a time of crisis.

All images courtesy Babita Sharma

All images courtesy Babita Sharma

Under Attack

Racial tensions were running high in the 1970s and 1980s and corner shops, then as now predominantly run by the Asian community, were on the frontline. We were soft, highly visible, vulnerable targets.

The ‘string of empty milk bottles on the door handle’ trick was much used in the Reading area to target Black and Asian households, including that of my parents – at the time a young couple settling into a new home and about to welcome their first child into the world. The perpetrator would tie the milk bottles to the door handle of the victim’s house, and when the victim opened the door in the morning it would cause the entire group of bottles to come crashing down and smash all over the ground.

There wasn’t much point in reporting these incidents to the police, dad was told. The local police station was dealing with dozens of similar cases with mounting paperwork and little time or desire to investigate what they called ‘time-wasters’. We called them racists.

Shutting Up Shop

In the 1990s, the trading laws changed, allowing bigger grocery stores to stay open longer and on Sundays.

We, the corner-shop families who had introduced an ‘open all hours’ culture to Britain, were buckling under the pressure of retail legislation and struggling to stay open at all.

The supermarkets were like special agents who for the past 50 years had secretly been hiding spies inside local corner shops, taking notes and reporting back to base on ways to corner the local market. They took our tricks of the trade, improved and refashioned them, then boldly passed them off as their own.

We may have started trading illegally on a Sunday, but it was the supermarkets and Prime Minister Thatcher that made the holy day of rest a thing of the past. Doing a food shop was no longer about popping to the local; it was now becoming a day out in glossy oversized stores with product overload. We were entering into a new phase of consumer culture and, after thirty years of business, the writing was on the wall for our family. It was time to shut up shop.

Image courtesy of Babita Sharma