Chinese Takeaway

Angela Hui

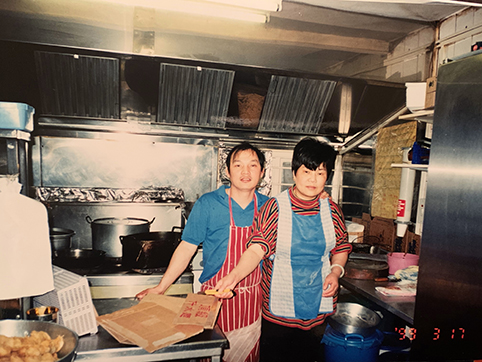

I grew up in a Chinese takeaway called Lucky Star, in the South Welsh valleys. From the age of eight, I worked alongside my parents and brothers, struggling to reach over the counter to serve customers and taking orders over the phone.

Chinese restaurants have deep roots in Britain. In 1908, a former ship’s chef called Chung Koon opened the first Cantonese restaurant, Maxim’s, in Soho. However, it wasn’t until 1958 that takeaways really took off. Chung Koon’s son, John, opened the Lotus House on Queensway. It became so popular that customers who couldn’t get a table asked to take the food home with them.

The majority of Chinese immigrants that came to Britain were from the Guangdong region. They set up takeaways across the country, living above their businesses and many taking over old fish and chip shops. Takeaway owners adapted to their British customers’ tastes by offering buttered bread, pies and chips alongside Cantonese dishes like egg fried rice and chow mein.

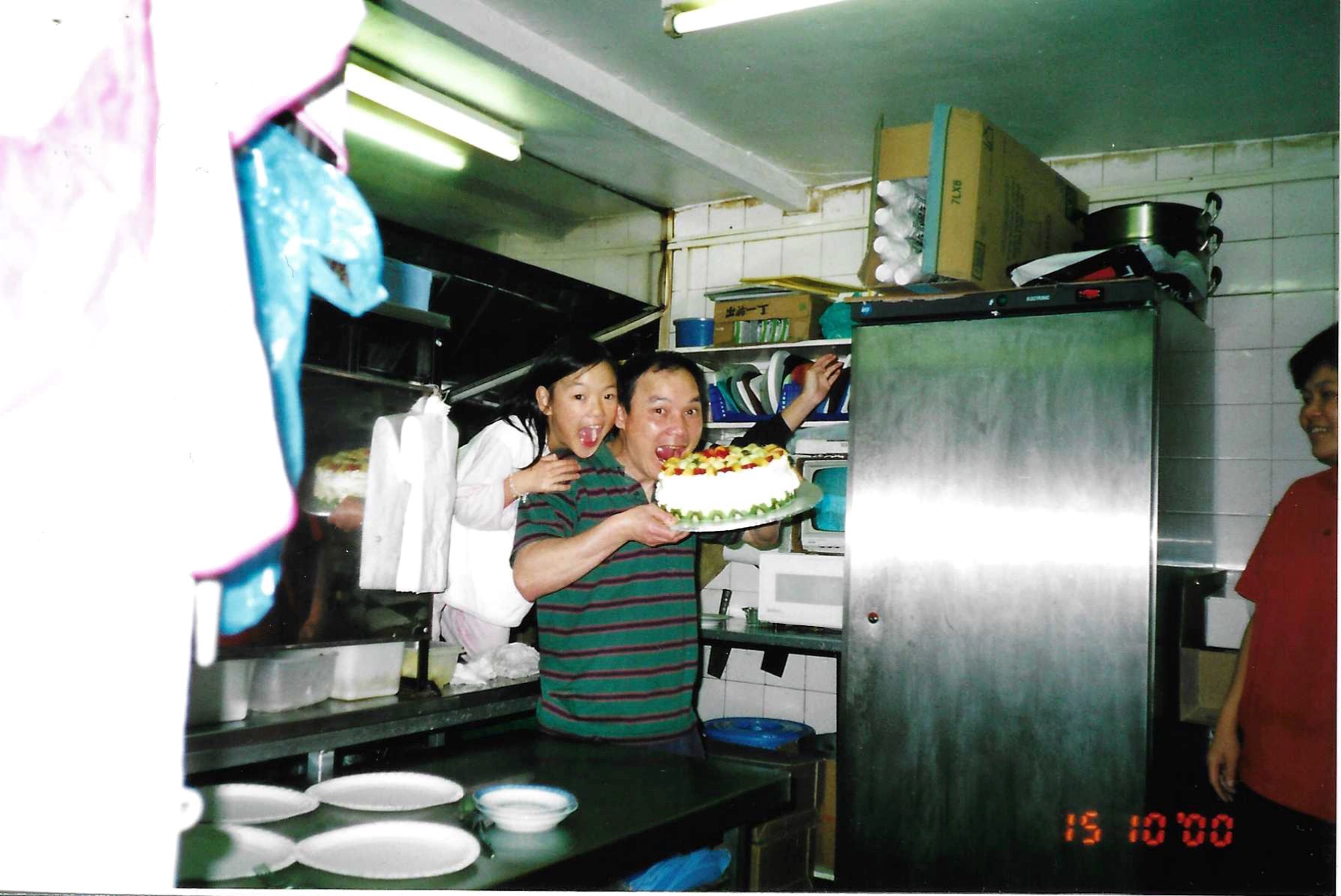

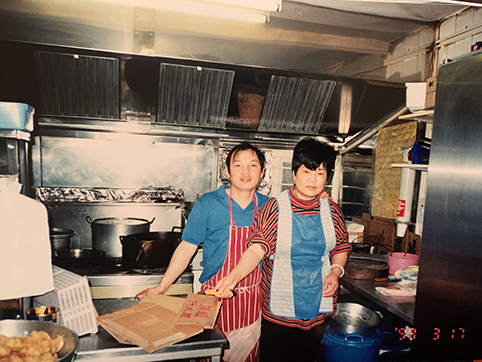

Image: courtesy Angela Hui

Images (above and top): courtesy Angela Hui

For my parents, like many others, working in a takeaway wasn’t about expressing a love for hospitality or cooking – it was about survival. It was how my parents made money to live and support our family. Takeaways were underpinned by colonialism, and British Chinese food developed under a determination for a better life despite the struggles faced. Sweet and sour pork and chop suey aren’t just delicious; they also tell stories of waves of immigration from Hong Kong, China, Vietnam and Malaysia.

This is a homage to the British Chinese takeaway that explores the idiosyncrasies of first and second generations and the blurred lives of families living and working in the same place.